When I was in third grade, my family visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was the first time I had been to a place like that. We had no familial ties to the Vietnam War—I'm the first American-born in my family—but it was still breathtaking, even to my nine-year-old self.

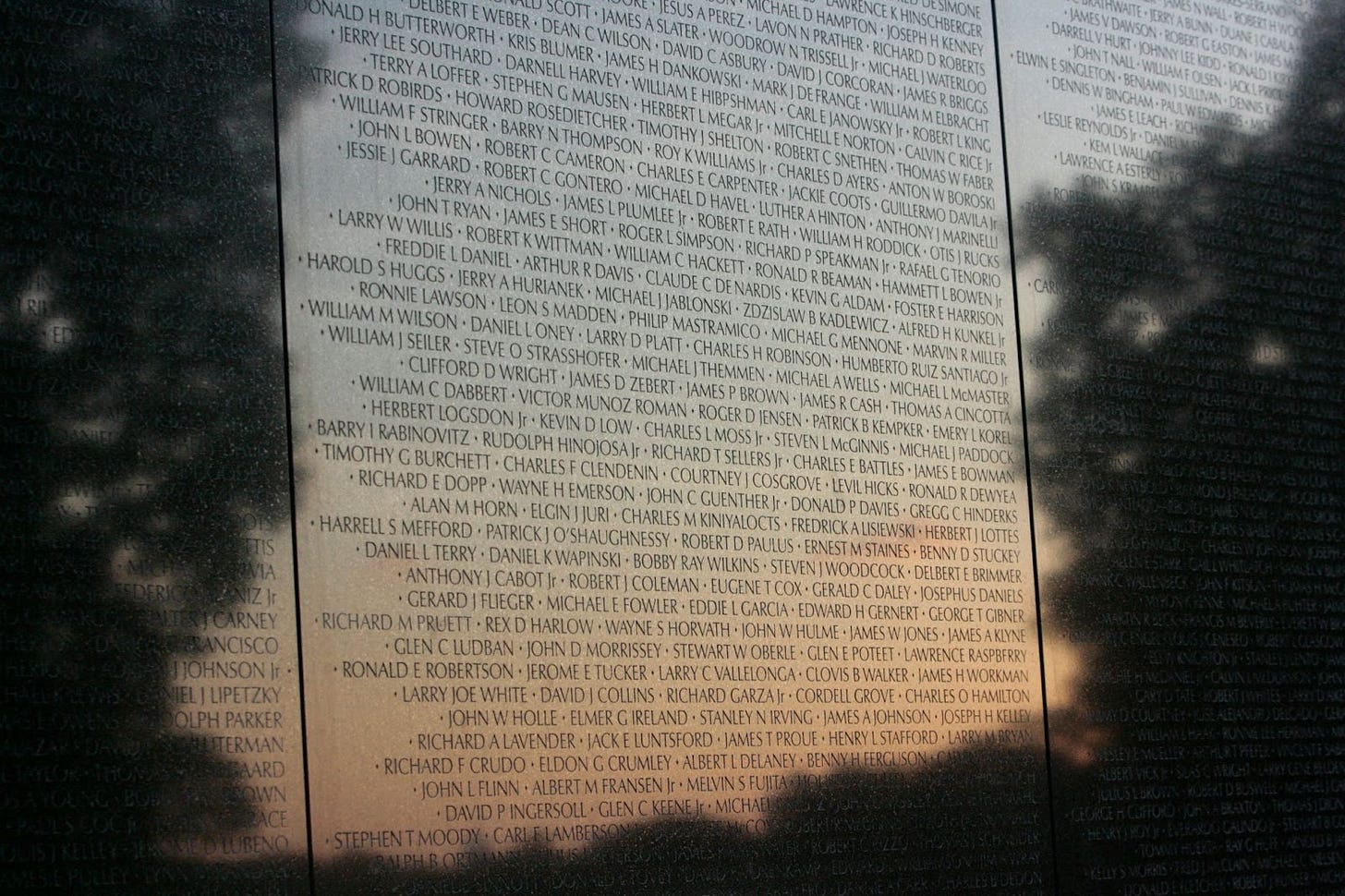

The V-shaped black granite. What felt like a never-ending wall of names.

There are so many, I thought. More than 58,000.

And each one represented a life.

The first time I remember feeling an awareness of how names can carry the weight of memory was a few years earlier, on a trip to Toronto. It’s where my dad was born and raised, and where his dad is buried. Most of my extended family still lived there, so we would visit once or twice a year, always staying with my grandma.

On each trip, we visited my grandpa’s grave. But first, we always stopped at a different cemetery—the one where my great-grandparents are buried.

It’s an older cemetery, so the plots are smaller. There wasn’t room for my grandpa and the larger caskets that came with modern death, so my grandpa was buried a few miles away at a newer, larger cemetery. That one is manicured, with edged grass and polished gravestones neatly spaced apart. But the old cemetery was different. The grass was overgrown, and the space was overcrowded with headstones that leaned into each other like drunken friends. Many were cracked, and it always seemed to be overcast when we visited. I was convinced ghosts came out at night.

My first memory of this cemetery was a few years before our visit to the Vietnam Memorial. I remember maneuvering over the uneven ground, in between the narrow rows of headstones, with images of Tales from the Crypt in my head.

“Here we are,” my dad said.

I looked up and saw gravestones all around me, many bearing my last name. I squatted down and stared at two of them.

Jenny Axler.

Sam Axler.

It was the first time I became aware of how a name represents a person, a life. These were people I’d never met, and yet they were connected to me. Without them, I wouldn’t exist. And yet all that remained of them—at least to me—was a name etched in granite. I didn’t know their stories. I would never know what made them laugh or how they lived. But their names were still there, and somehow, that meant something.

Flash forward two years, and I stood in front of more granite—this time reading the names of more than 58,000 men and eight female nurses who were killed in Vietnam or went missing in action. I didn’t know them either, but even though we weren’t related, I felt connected to them.

Robert D. Snyder

Johannie L. Garner

Eleanor Grace Alexander

Who were they? What made them laugh? How did they live their life?

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial was designed by Maya Lin, an American architect and sculptor. Like the war itself, her design was controversial. It broke from tradition—no statues of generals, no triumphant poses. Just a wall, carved with names. A traditional statue depicting three servicemen with a flag was eventually commissioned to sit at the entrance to the memorial, but it’s the wall that stops time. It’s the wall people find themselves standing in front of longer than they expected.

That was true for me. I remember running my fingers along the engraved letters, as if that could somehow bring them to life. I imagined who these people were, what they might have done if they had lived. I only knew their names because they had died.

When we talk about the casualties of war—or of pandemics, disasters, or any mass tragedy—we often reduce lives to statistics. Death tolls help us capture the magnitude of loss, but they also swallow the individual lives comprising those numbers. They flatten individuality. We lose sight of the fact that behind each number was a whole life: someone who laughed, cried, hoped, and was loved.

What the Vietnam Memorial did was flip that notion on its head. As Peter S. Hawkins wrote, “The memorial turned numbers into names.” That’s why other memorials—like Yad Vashem, the 9/11 Memorial, and the AIDS Quilt—use names, too. Because names humanize, they resist forgetting.

It’s said that a person’s name is their immortality. It’s how we live on, even after we’re gone. More than that, a name is proof that we existed.

Humans have always wanted to be remembered. In the book of Ecclesiasticus, it says:

There be of them, that have left a name behind them,

That their praises might be reported.

And some there be, which have no memorial;

Who are perished, as though they had never been,

And are become as though they had never been born,

And their children after them.

We want to be remembered. And our names are often how we are. In many ways, names are the only things that make us real to those we will never meet.

They are proof that we were someone with a life story of our own. That we are worth remembering.