Where is my name?

on ownership and identity

Last Tuesday, my computer died when I was supposed to be writing. Since I rarely leave the house without a notebook, I decided to go analog. Instead of grabbing the yellow one I’ve been using for the past year, I pulled out the green one, filled with old notes and ideas.

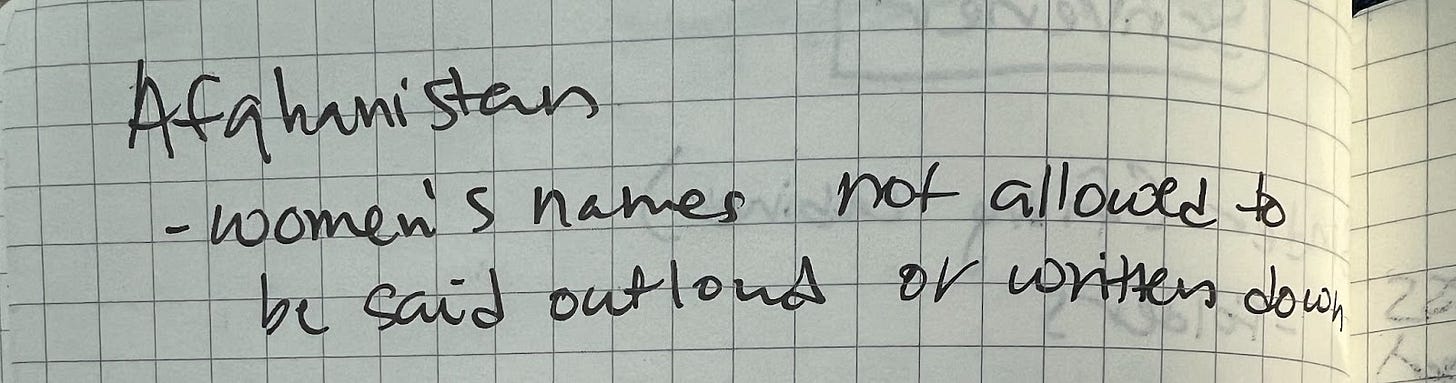

I flipped it open to a random page, where I saw a few notes about Icelandic naming traditions on the right side. They are unique and interesting, and I should write about them soon. But a quickly scribbled note on the left page caught my attention.

I remember reading this and not fully believing it could be true. At the time, I was researching something else, so I jotted down the information with plans to return to it later. That was over two years ago, and somehow, I'd forgotten about it despite loosely following Afghan women’s suppression since the Taliban regained power in 2021.

I’ve read about the banning of girls' education past sixth grade, the elimination of most female employment, and the forbidding of girls in parks, gyms, or sports. I learned that it is illegal to hear a woman’s voice in public, and just this past December, the Taliban banned windows overlooking spaces often used by women. Yet none of these reminded me of the most basic erasure of all: not calling a woman by her name.

In Afghanistan, it is considered disgraceful for a woman’s name to be spoken aloud or written down. Afghan women are forced to keep their names secret from people outside their families. For Afghan men, revealing the names of their female relatives in public is considered shameful and dishonorable. When this rule is broken, the result is often violence, particularly towards women.

Sociologists say the practice comes from a tribal belief that a woman’s body belongs to a man. Therefore, her identity comes from relationships with men, whether a father, a husband, or a son; they own her, like a goat or a house. Saying her name out loud, or even knowing her name, dishonors them.

When planning my wedding, I got angry when my parents wanted to address the invitation envelopes to “Mr. and Mrs.” his name. “We cannot do that,” I said. “It’s creepy and weird to address a woman by her husband’s name. She has her own name, which should be included, too.” My dad, surprisingly, understood my point. It was my mom who took a little convincing. “That’s the formal way of doing it,” she said, but in the end, I won. Looking back at how upset I was over an envelope, I can't imagine what it’s like not to be called by your name in every other aspect of life.

It’s unclear whether this practice began with the Taliban or earlier—the lack of information on it is troubling. But, before 1979, women in Afghanistan had a similar level of freedom to women in other countries (for context, they got the right to vote a year before women in the US did). But in 1978, when the president was killed in a Soviet-supported coup, a more liberal government took hold, and women were allowed to get an education or choose not to wear a hijab. This created a backlash from religious fundamentalists, which kicked off a decade-long war, ending with the Taliban gaining control in the 1990s.

Once that happened, women were systematically erased from society and reduced to their relationships with men. Many girls, from a young age, are conditioned to believe that they are just an extension of a man, with no independent identity of their own.

When girls are born in Afghanistan, they often aren’t given a name for weeks, sometimes longer, because of the social stigma associated with publicly revealing a female’s name. They are usually identified by their relationship to a man—“daughter of” or “wife of”—so giving her a name doesn’t feel as important.

Thinking about my last post, I can’t help but notice the contrast: how the celebration and care in choosing a girl’s Hebrew name gained more popularity since the 1980s when, around the same time, the erasure of females from Afghan society was being ramped up.

Saying a woman’s name in public isn’t the only thing that is forbidden; women’s names are not included on national ID cards or recorded on their children’s birth certificates. According to Afghan law, only the father’s name is recorded on a birth certificate, making it impossible for mothers to enroll their children in school, get passports, or make medical decisions.

When men take their wives or daughters to the doctor, they often won’t share their names with the medical staff; prescriptions are filled without the woman’s name on the bottle. In many cases, the shame of saying a woman’s name is so profound that even husbands often refer to their wives as “mother of” one of their children’s names rather than their actual name.

Throughout a woman’s life cycle, she is referred to in public by her relationships with men.

When she is born, she is identified by her father as the “daughter of.” When she gets married, her name is not on the marriage announcement or documents, and she becomes identified by her husband as “wife of.” When she gives birth, there is no reference to her being the mother on any documentation, but her name becomes “mother of.” And when she dies, she will be remembered, most likely by her husband’s name; her name will not appear on her death notice or tombstone.

Women are seen as the property of their fathers, then their husbands, then their sons.

Frustrated by this tradition's inhumanity, Afghan women began challenging it in 2017 during a break in Taliban rule. Laleh Osmany started the #whereismyname campaign on Facebook to remove the shame from women’s names, highlight the importance of recognizing women’s identities, and advocate for gender equality. Many Afghans, including popular singers and some politicians, embraced the movement.

My eyes watered when I read what one Afghan refugee wrote on social media. “I am proud to write that my name is Sahar. My mother's name is Nasimeh, my maternal grandmother's name is Shahzadu, and my paternal grandmother's name is Fukhraj." This was probably the first time she said those names out loud. I read them out loud, too, thinking about how strange, scary, and exhilarating it must have felt to do something so simple and fundamental.

The campaign didn’t just advocate for calling women by their names; it also demanded that mothers’ names be included on their children’s birth certificates. In 2020, despite a lot of resistance and criticism, after three years of campaigning, the then-president signed a decree allowing women’s names to be included on their children’s ID cards. It might not seem like much, but it was a historic first in Afghanistan and challenged and changed a generational taboo. It also gave mothers rights to their children, which is significant.

For her work on this campaign and for advocating for Afghan women's rights, the BBC chose Laleh Osmany as one of the 100 most influential women in the world in 2020.

Within months of the decree, however, the Taliban regained power and began systematically rolling back the rights of women, ensuring they remained invisible and powerless. Laleh Osmany, who received many threats of violence for her campaign, moved to Germany.

As far as I can tell, women’s names are still on their children’s ID cards, but I don’t know if the Taliban undid that. I could say it doesn’t matter since women can’t show their faces in public or leave the house without a male family member, but it does matter. Mothers who bear, give birth to, and feed their children should be acknowledged for this role. All women are entitled to their own identity, free from their roles and relationships with men.

Our names belong to us.

I want to do more to help Afghan women, but I don’t know how. I figured the least I could do was tell this part of their story and, when possible, say their names out loud.